In mid October thru mid November, Flint and I traveled extensively through California, Arizona and Texas and back to California training and competing in hunt tests. At the end of November, Flint began to show symptoms of some sneezing that developed into a cough. On December 7, 2009 Flint was treated for a respiratory infection. On December 14 there was a noticeable lump on Flint’s left side on his rib cage. It was soft and movable. The lump was examined and determined to be a possible injury with a secondary infection. X-ray of the lungs showed a lot of inflammation with a granuloma. Bronchitis was diagnosed. Flint was placed on the antibiotic Baytril for several days with no response. Amoxicillin was added with no change. Flint was not feeling well and not eating well. We started monitoring his temp.

On 12/20/2009, Flint was admitted to UC Davis Vet School with 105.4 degree temperature. Blood work showed that Flint had an active infection. Ultrasound scan of Flint’s abdomen proved unremarkable. The mass on the left side had a bright center on ultrasound, but a foreign body could not be ruled out. On 12/21/09, Flint was anesthetized for CT SCAN and bronchoscopy with cytology and culture. CT Scan showed consolidation of the right cranial lung lobe. The bronchial lymph nodes were enlarged, especially on the right side. Smaller nodules were seen throughout the remaining lung lobes. Bronchoscopy showed that the lungs were inflamed, especially the right cranial lung lobe. The camera could not pass to the area where the thickened lung lobe was seen on CT. The airway near the enlarged lymph nodes was completely compressed. No foreign bodies were seen. Sterile water was flushed into the lungs and collected for microscopic evaluation and fungal and bacterial culture. The fluid from the lung lobes contained cells suggestive of mild inflammation. Fluid samples from the lungs were submitted for culture. Ultrasound was used to visualize Flint’s right lung. A needle was used to aspirate cells from the affected portion of the right lung. No bacteria or fungi were seen in the sample, but the type of cells seen in fungal infections was numerous on the sample. A blood sample was submitted to test for Valley Fever, Coccidioidomycosis.

December 21, 2009 Flint was diagnosed with Coccidioidomycosis more commonly known as Valley Fever. Yes, dogs get Valley Fever! Like people, dogs are very susceptible to Valley Fever. The good news is that Valley Fever is treatable. The bad news is that it is not always curable and treatment may be a lifetime. Early detection & Flint’s response to medication has helped his extraordinary recovery and his return to AKC hunt test competition. Following the protocol advice from Dr. Lisa Shubitz of the Valley Fever Center for Excellence and the Veterinary Specialty Center of Tucson, My vet Dr. Sharon Talley was able to treat Flint at my clinic with IV lipid based Amphotericin B 3x/week for 3 weeks. Flint was then placed on the oral anti-fungal medication, Fluconazole which he still continues today. Holistic supplementation has also helped to keep all his blood values in check. After 3 months, Flint is back competing again.

In October 2010 Flint passed the AKC Master National in his first attempt. It was a highlight of his young career. Shortly after the completion of the National, we took Flint off his medication. Since he had done so well and titers were negative there was reason to believe that Flint could be fungal free without medicine. At the end of November, the Cocci titer still showed negative. At the end of December the titer was slightly elevated but noone was overly concerned as that could be a residual for having been exposed previously. By January Central Nervous System symptoms became apparent and Flint was taken to VCA. His temperature was elevated and he was showing back pain. A CT scan showed a C6-C7 fusion (old injury) and a MRI showed inflammation. A spinal tap was the definitive diagnosis for Valley Fever in the Spinal Fluid.

Flint had relapsed and he had the most lethal form of Valley Fever, Cocci Meningitis. So began the long treatment regime to try and save his life. Without treatment, he would surely die and even with treatment he could die. He was treated with IV Ambisome as it penetrates the blood/brain barrier into the Spinal Fluid. He was also put on high doses of Fluconazole to hit the Fever with everything we had. Flint showed CNS symptoms and at times he would lose control of his rear legs and drool. When he would refuse to eat, I would have to force feed him. Things looked bleak but slowly, Flint began to turn around. The IV treatments ended March 7, 2011. He was then placed on a Posaconazole, an oral fungal medication. 3/18/11 Flint started showing side effects from the Posaconazole. It was disconinued and he was placed on his old medication Fluconazole. So far it is holding and the CNS symptoms are subsiding. Unfortunately Flint's fantastic career is being cut short by the relapse of the Valley Fever and the possibility of paralysis from the Cervical vertebrae fusion, should he continue field work. He has accompished so much in such a short time but his life is way more important than any of it. Flint is officially retired from competition to relieve him of any stress and hopefully give him a chance at a long, fulfilled life as my buddy. Hope an prayers continue for Flint's recovery.

Valley Fever is caused by a fungus that lives in the desert soil. As part of its life cycle, the fungus grows in the soil and matures, drying into fragile strands of cells. The strands are very delicate, and when the soil is disturbed by digging, walking, construction, high winds - the strands break apart into tiny individual spores. Dogs and people acquire Valley Fever by inhaling these fungal spores in the dust raised by the disturbance. The dog may inhale only a few spores or many hundreds.

Once inhaled, the spores grow into spherules (parasitic cycle) which continue to enlarge until they burst, releasing hundreds of endospores. Each endospore can grow into a new spherule, spreading the infection in the lungs until the dog’s immune system surrounds and destroys it. The sickness Valley Fever occurs when the immune system does not kill the spherules and endospores quickly and they continue to spread in the lungs and sometimes throughout the animal’s body. About 70% of dogs who inhale Valley Fever spores control the infection and do not become sick. These dogs are asymptomatic. The remainder develops disease, which can range from very mild to severe and occasionally fatal.

Symptoms

The most common early symptoms of primary pulmonary Valley Fever in dogs are:

• coughing

• fever

• lack of appetite

• lack of energy

• weight loss

Some or all of these symptoms may be present as a result of infection in the lungs. As the infection progresses, dogs can develop a severe pneumonia that is visible on x-rays. Sometimes the coughing is caused by pressure of swollen lymph nodes near the heart pressing on the dog’s windpipe and irritating it. These dogs often have a dry, hacking or honking cough that resembles bronchitis. Additional symptoms develop when the infection spreads outside the lungs and causes systemic or disseminated disease. This form of Valley Fever is almost always more serious than when confined to the lungs.

Signs of disseminated Valley Fever can include:

• lameness or swelling of limbs

lameness or swelling of limbs

• back or neck pain

back or neck pain

• seizures and other manifestations of central nervous system swelling

seizures and other manifestations of central nervous system swelling

• soft swellings under the skin that resemble abscesses

soft swellings under the skin that resemble abscesses

• swollen lymph nodes under the chin, in front of the shoulder blades, or behind the stifles

swollen lymph nodes under the chin, in front of the shoulder blades, or behind the stifles

• non-healing skin ulcerations or draining tracts oozing fluid

non-healing skin ulcerations or draining tracts oozing fluid

• eye inflammation with pain or cloudiness

eye inflammation with pain or cloudiness

Some of these symptoms are very rare and most need to be differentiated from other diseases of dogs. Still other signs can develop that are referable to affected internal organs and may only be detected by your veterinarian. While the lungs are the most common site of Valley Fever in dogs, it can infect almost any tissue of the body. Sometimes a dog will skip any signs of having a primary infection in the lungs. The dog may develop symptoms of the disseminated disease, such as a swollen, lame leg but no cough or fever. He may develop fever, weight loss, a draining tract, but may continue to eat well and have no cough.

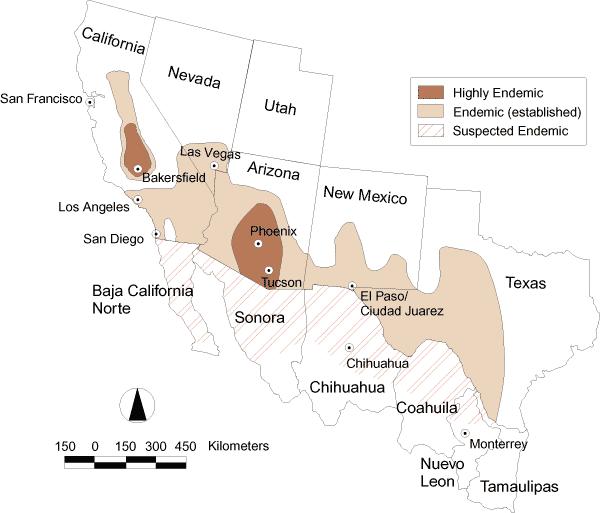

Valley Fever is a condition unique to the dusty regions of the southwestern United States. It typically affects the low desert regions encompassing central California, Arizona, New Mexico and Southwestern Texas. It is Highly Endemic to Phoenix and Tucson, AZ as well as Bakersfield, CA. Symptoms occur within 7-21 days of travel to these areas.

Much of this information was obtained from the Valley Fever Center for Excellence website at: http://www.vfce.arizona.edu/VFID-home.htm